Playback Singing in Bollywood Movies

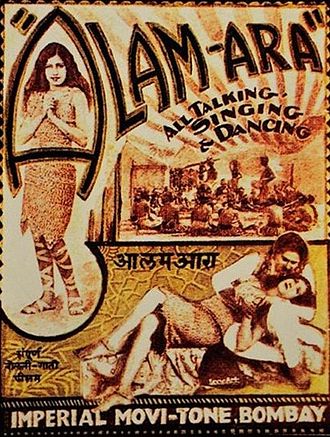

Bala Joban was the first Indian movie with sound and dialogue (“talkie” movie) to be shown in Trinidad. It was released in India in 1934 and shown in Trinidad in 1935. However, Alam Ara was the first Indian movie with sound to be produced in India. It was released in 1931 and was considered a breakthrough for the Indian film industry. Its seven songs were the first to be featured in an Indian movie. Subsequent movies increased the number of songs. For example, the second Indian movie with sound, Shirin Farhad, released in 1931, featured 18 songs. The following year, the musical, Indra Sabha, was released and featured 72 songs!

Music became an integral part of movies in India ever since and eventually the song-dance routine gave Indian cinema its unique identity (Sen, 2016). In later movies, the songs were reduced in number and were made more appropriate to the context of the story. For example, Bala Joban had 15 songs. The average number of songs per movie between 1931 to 1940 was 10 (Splice Blog, 2022).

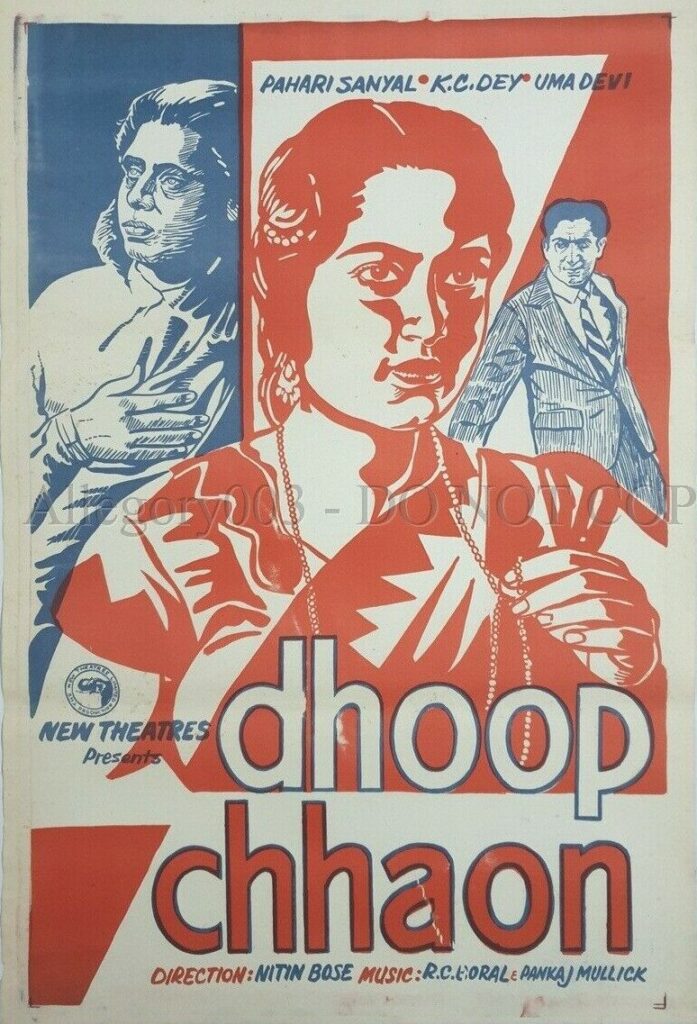

In 1935, the same year that Bala Joban was shown in Trinidad, the movie, Dhoop Chhaon introduced the concept of playback singing to the Indian film industry. A playback singer, also known as a ghost singer, is a professional singer whose voice is pre-recorded for use in movies. Actors and actresses lip-sync the songs during the picturization or filming of the songs (Splice Blog, 2022; Gooptar, 2014).

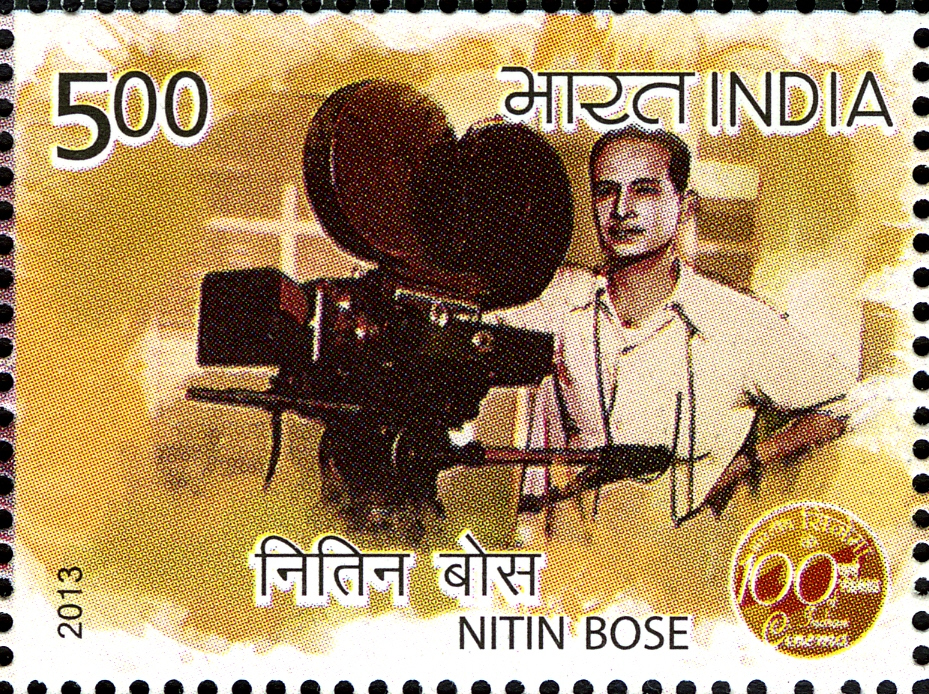

The director of Dhoop Chhaon, Nitin Bose (1897-1986), came up with the idea for playback singing and discussed it with the music director, Rai Chand Boral, and his brother, Mokul Bose, who was the sound recordist at the New Theatres production studio (Indian Baja, 2010). Through the efforts of Mokul Bose, the musical directors Rai Chand Boral and Pankaj Mullick, lyricist Pandit Sudarshan, and singers such as K. C. Key, Uma Shashi, Pahari Sanyal, K. L. Saigal, and others, the brainchild of Nitin Bose became a reality. The movie featured 10 songs. One of the songs from Dhoop Chhaon is featured below.

At this point, you are probably wondering, how were songs recorded in the movies that came before Dhoop Chhaon? In those movies, actors and actresses sang their own songs, on set, and the musicians played on set too — often hidden behind trees and other props on the set! (Saxena, 2020; Beaster-Jones, 2015). At the time, recording technology could only record a limited portion of the sound spectrum perceptible to the human ear, so the recordings focused on the human voice and a limited set of musical instruments (Beaster-Jones, 2015). Interestingly, actors were often chosen for their singing abilities (Indian Baja, 2010). Not every actor could sing, though. In Booth (2008, p.42), it is reported that in a letter to a film magazine in 1940, a writer had requested “Ashok Kumar to stop singing in pictures”.

Booth (2008, p.43) quotes music director Naushad Ali (1919-2006) as saying that,

“Once playback came in, it was no longer important that the actors could sing. They could do their work [acting], and somebody else could sing.”

Naushad Ali- Music Director

However, it took several more years before the total separation between actors and playback singers occurred. Until 1947, many movie stars continued to do their own singing. Some actors based their careers more on their abilities as singers than as actors. Booth (2008) suggests that K. L. Saigal might fit into this category as well as the great vocalist and film heroine Noor Jehan. Booth also claims that Suraiya, who became a very popular actress, began her film career as a singer. Until the early 1940s, singing actors outnumbered playback singers. In 1936, the ratio of recordings by playback singers to those by singing actors was one to three. By 1946, the ratio was more than three to one. This was due to the steady growth in the number of specialist playback singers that took place over the previous ten years and a sharp decline in number of singing actors over the previous four years (Booth, 2008).

1947 became a turning point for playback singing. India’s most famous singing star, K. L. Saigal, died in January that year, and the reigning female singing star, Noor Jehan, went to Pakistan after the Partition, leaving behind a huge void in playback singing (Saxena, 2020). That void was filled by two singers who went on to become legends in playback singing: Lata Mangeshkar and Mohammed Rafi. Playback singing had now become the lifeblood of Indian movies (Gooptar, 2014). By the 1950s, the leading playback singers had also become stars in their own rights (Booth, 2008).

The following paragraphs give some more information on playback singing in Indian movies. The paragraphs are mostly derived from (Gooptar, 2014, p.237-238, with permission) and highlight the role of the mike men in publicizing playback songs throughout Trinidad.

The institutionalisation of playback singing in Indian movies after Dhoop Chhaon provided many opportunities for the creativity and geniuses of not only the music composers, but the lyricists, musicians, music directors and the playback singers to blossom. Many fans went to see Indian movies because of the songs and dances. The playback singers seemed to sell and sustain the movies with their songs. Many Indian movies owe their success to the playback singers and musicians. Mediocre movies such as Dil Dekhi Dekh, Silsila and Junglee with poor story lines became successful because of the extremely popular songs.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Indian playback singers such as K. C. Dey, K. L. Saigal, Suraya and Shamshad Begum were very popular both in India and Trinidad. However, in the 1950s, Mohammed Rafi, Mukesh, Lata Mangeskar, Asha Bhosle, Hemant Kumar, Manna Dey and Kishore Kumar took over and dominated playback singing in the industry for the next few decades. With the coming of Indian programs on radio in Trinidad in 1947, those singers became even more popular and their songs were on the lips of all lovers of Indian movies and Indian film songs. This period, often called the Golden Era (1949-1969), was completely dominated by Mohammed Rafi and Lata Mangeshkar and to some extent, Hemant Kumar, Asha Bhosle, Manna Dey and Kishore Kumar. In later years, singers such Alka Yagnik, Kumar Sanu, Udit Narayan, and Kumar Sanu made their mark in the industry and became very popular among the younger generation of the 1990s and beyond.

In most instances, the songs were known and popularized in Trinidad before the movie was released. In the 1950s and 1960s, before an Indian movie was released in Trinidad the local record shops received advanced sample copies of the songs from the movie distributors. The record shops sent messages to the mike men to visit the record shops for a copy of a new song from a new movie. The record labels were color coded. The blue label record was usually a sample copy while the red or orange label records were for sale. The mike men were given the blue label record and they played the songs on their mikes throughout the island. This helped to boost the sales of the records and popularized the movie before its release in Trinidad.

Two of the major record shops in the early days of Indian movies in Trinidad were Razack’s Indian Records in San Juan and Balroop’s Record Shop in Arouca. The songs were generally released to the mike men between six months to one year before the movie was released on the island. When radio and television became popular the songs were then popularized through those media, but the mike men continued their work throughout Trinidad, playing their songs everywhere they went. The mike men held a special appeal to the people, especially in the rural communities and wherever they went, they always had an audience.

Did you know?

Crediting playback singers started with Lata Mangeshkar in 1949 (Beaster-Jones, 2015). Fans clamoured to know who sang the haunting and beautiful song, Aayega Aanewala, from Mahal, even writing letters to All India Radio (Saxena, 2020; Beaster-Jones, 2015). Lata pushed to be given credit, too. This resulted in the second batch of the record covers for Mahal being changed to credit Lata. Thereafter, crediting playback singers became the norm (Beaster-Jones, 2015). For example, when the soundtrack of Barsaat was released in 1949, it featured the names of the singers. Beaster-Jones (2015, p.80) goes on to suggest that the appearance of the names of playback singers on recordings from 1949 onwards was “the pivotal point when playback singing was fully accepted by Indian audiences”.

We conclude this article on playback singing by featuring the song, Aayega Aanewala, from Mahal.

References

Beaster-Jones, J. (2015). Bollywood Sounds: The Cosmopolitan Mediations of Hindi Film Song. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Booth, G. D. (2008). Behind the Curtain: Making Music in Mumbai’s Film Studios. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Gooptar, P. (2014). The Impact of Indian Movies on East Indian Identity in Trinidad. Saarbrücken, Germany: LAMBERT Academic Publishing.

Indian Baja (2010). Vintage Film: Dhoop Chhaon (1935). Available from: https://indianbaja.wordpress.com/2010/03/09/vintage-film-dhoop-chhaon-1935/.

Saxena, P. (2020). The Way We Were: Lata and the Dawn of the Playback Era. Hindustan Times, August 16, 2020.

Sen, S. (2016). 85 years of ‘Alam Ara’: How India’s First Talkie Paved the Way for Song-Dance Routines in our Films Forever. Available from: https://www.news18.com/news/movies/85-years-of-alam-ara-how-indias-first-talkie-paved-the-way-for-song-dance-routines-in-our-films-forever-1215897.html

Splice Blog (2022). The History and Evolution of Bollywood Music. Available from: https://splice.com/blog/history-bollywood-music/